Lands and Horizons

Statement

A PERCEPTIVE AND SYMBOLIC GEOGRAPHY

From a specific point in the territory, we can observe a circular space that contains us. This perception of a circle —sometimes clearly delineated by the horizon, other times interrupted by urban structures or natural features— refers to the practices of Land Art, where the environment becomes support, material, and meaning.

Thus, from this fixed point—the observation point—space is revealed not as something static, but as a perceptual construction: a geography that is transformed by gaze, time, and movement.

Land art artists began to experience this circularity as a fundamental form of perception when working directly in open landscapes. In this context, the horizon is naturally perceived as a circular line surrounding the observer in all directions.

The notion of the horizon, studied by Merleau-Pontyl, transcends the idea of a distant line to become a mobile and enveloping limit of all experience. This horizon moves along with the body, placing the subject at the center of a perceptual sphere that articulates and defines their embodied relationship with space and time. In this sensory experience, the landscape is no longer contemplated from the outside; one is immersed in an enveloping space that extends in all directions.

The central point organizes space, invites contemplation and experience, and is the beginning of everything that can be observed. It is more than a geographical reference; it is the origin from which the landscape unfolds, every direction opens up, and every horizon becomes reachable.

In the center of the circle, the world opens up,

like a rose unfolding before our eyes.

There is no path, only a beginning.

There, forms awaken,

time folds, the horizon extends,

and everything that is not yet begins to be.

Thus, the Earth reveals itself not as a single world, but as a constellation of worlds united by a moving center: the consciousness of the one who contemplates it. That central point changes with each step, with each height, with each focus of attention. It is not fixed on the map, but in the encounter between the eye, the terrain, the horizon, and the symbolic.

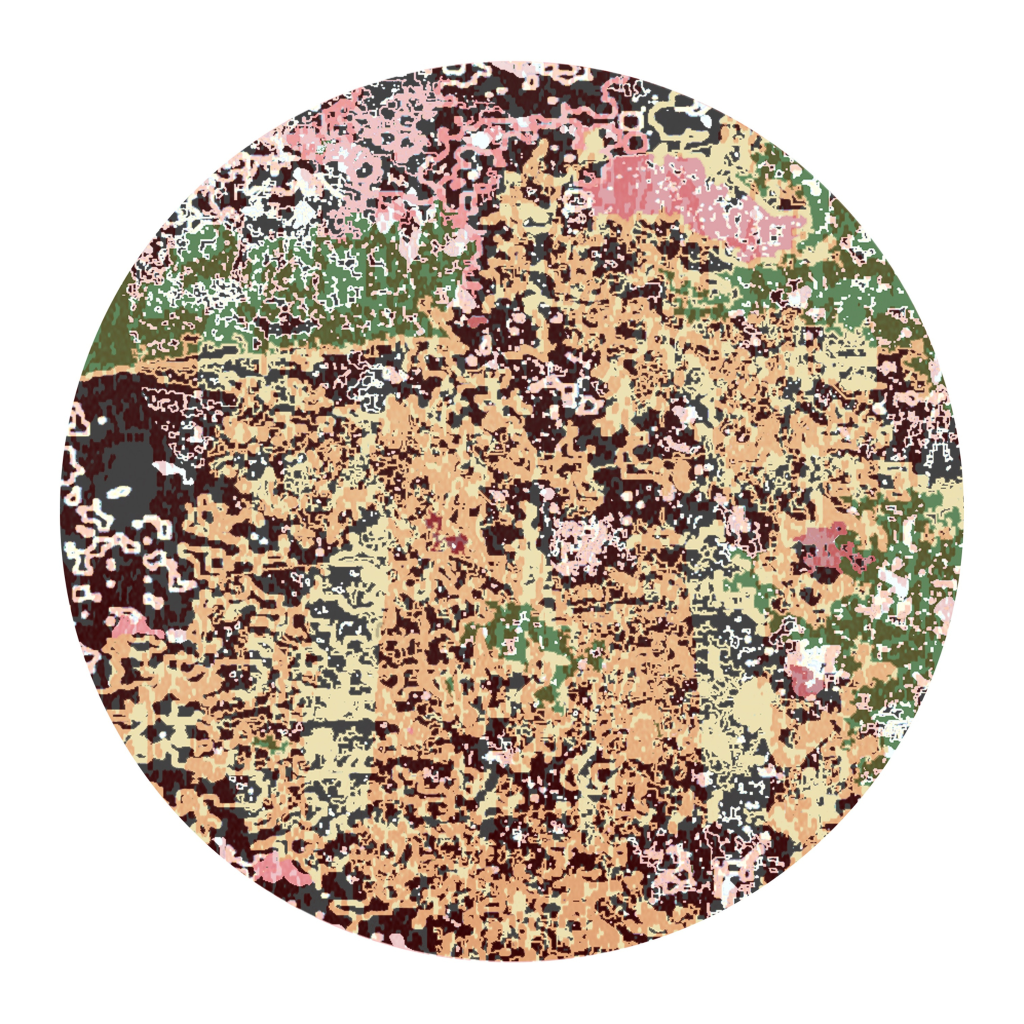

My project Lands and Horizons is a series of prints that proposes a symbolic and sensory exploration of the territory. Each image constructs a possible world, an atmosphere. These are not real maps, but spaces born from the intersection of experience, memory, color, and form. Imagined territories where the landscape becomes language and the surface of the earth a living drawing.

This experience of inhabiting the landscape refers directly to the idea of Peter Sloterdijk, who proposes in his trilogy Spheres that human beings do not simply occupy a physical space, but create and exist within symbolic and existential “spheres” that give meaning and protection to their vital world. In this vein, the horizon can be understood as a boundary within this lived sphere, which is both a limit and a connection to the outside, a space that is constructed in interaction with others.

The prints appear as bird’s-eye view images. What could be scattered fragments are reorganized around a shape: a circular horizon. At the center of that circle—not necessarily visible, but present—lies the essential point. Seen from above, the circular horizon is transformed into an earthly mandala: a drawing is revealed as a living geometry of lines, spots, colors, and textures that dialogue with each other to compose a world.

This opens up the possibility of thinking of the territory as an active field of relationships and meanings. Each print represents a world, thematic spaces that condense ways of seeing, feeling, and inhabiting the landscape. They are affective topographies, symbolic territories that emerge from embodied experience and are projected onto the earth as a succession of symbolic spheres that human beings construct to give meaning to and protect their existence.

In this vein, each print in Lands and Horizons can be understood as a micro-sphere, an “expanded interior” onto which imaginaries, desires, conflicts, and sensitive states are projected. They are symbolic atmospheres: Interfered Land, Hostile Land, and Camouflaged Land speak of political and territorial tensions; Dream Land, Night Land, and Land of Roses evoke dreamlike or poetic spaces; Illustrated Earth and Narrated Land reflect on how territory is constructed by language and image.

Together, these images form an existential cartography, a constellation of possible worlds that do not exist without the subject who inhabits, imagines, or names them. And as in Merleau-Ponty, these worlds are not offered as external objects, but as phenomenal fields that are revealed through the body and its relationship with the environment.

Lands and Horizons is not a series of landscapes; it is a proposal to think of territory as a form of living, mutable, and relational experience. A terrestrial mandala that, when viewed from above, from within, or from memory, tells us how space is not only traversed, but also perceived and interpreted.